Jose Angel Garcia

PhD Researcher, Department of Politics

University of Sheffield.

A couple of weeks ago Matthew Wood wrote an interesting post about what seems to be the contemporary “crumbling” in confidence in democracy around the world; a disenchanment fuelled by a “ceaseless government accountability”. Wood’s point is similar to Flinders’ argument in Defending Politics, which states that societies around the world are living in an era of high governmental accountability which, ironically, has produced the unintended effect of a generalized and increasing political distrust among the population. In other words, more information creates more questions. This constant skepticism or “corrosive cynicism” towards politicians has a twofold effect; on the one hand, citizens with increasing demands, bigger expectations, but less willing to cede rights or give more power to politicians. On the other hand, politicians locked in a “no-winning” game, where political competition, finger-pointing and a major public scrutiny, has forced them to inflate their political promises, giving more opportunity for future political disappointment.

Nevertheless, it is undeniable that accountability is a necessary condition for the development of a healthy –and I would argue, more effective democracy and a major confidence in politics. As noted by Helvia de la Jara (http://inicio.ifai.org.mx/Publicaciones/Transparencia_y_Confianza14.pdf, trust; therefore, political trust can only flourish in a society free of fear, where uncertainty is at its lowest possible level, and where political institutions demonstrate their capacity to act. Then, it is only through accountability processes that it is possible to establish and determine the levels of confidence over institutions, ensure their compliance with their socio-political objectives, and guarantee their institutional consolidation, even continuity. By knowing the what for, for whom and how, society and government can decide over the existence and efficiency of institutions, and identify and penalize any of their possible deviations, which otherwise would be detrimental for a country’s democratic development. Several cases can be analyzed to demonstrate both the positive and negative political effects of an “over accountability”. Nonetheless, I will limit myself and refer to the Mexican case.

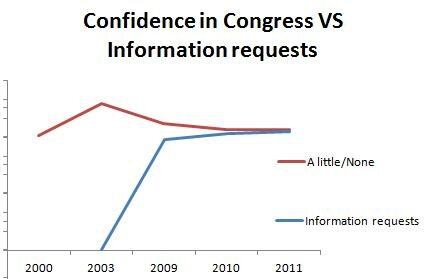

Mexico, which became an “internationally accepted” democracy in 2000, has been recently recognized for its Institute for Transparency and Accountability (IFAI). With an increasing number of public information requests, from an average of 24,097 in 2003 to almost 110,000 in 2013, this federal institute is now fully autonomous and has one of the biggest budgets in the sector in the world (almost £24,000,000). Although it has become a precedent in government openness and accountability, the situation in Mexico is not quite different from other countries where, paradoxically, a major accountability tends to be accompanied by a major disenchantment or distrust in politics.

As the OECD states, trust is a very subjective issue, but key for the functioning of any government and the efficiency of its public policies. Therefore, it is important to make a distinction between politics, politicians and what people consider “the” government in general. Regarding politicians in Mexico, in 2000, three years before the creation of the IFAI, 3% of the population trusted the Congress “a lot”, 18% “more or less”, 34% “a little”, 44% “nothing” and 1% “didn’t know”. By 2011 there were less people trusting the Congress than 16 years before, but more people who trust on it since the beginning of the Mexican accountability era in 2003.

Although the peaks in public confidence in Congress match the declines in the number of information requests, it would be too simplistic, even unscientific to establish a correlation between –a possible over– transparency or accountability and public confidence in the Congress. As Flinders points out, too many external forces have an effect over societies’ perceptions and demands, such as economic crisis, increasing education levels, media negative or positive over-coverage, etc., which can augment or reduce public confidence in politicians, government institutions, democracy and politics itself. This is why promoting the understanding of politics by the population has been considered a necessary condition for the development of stronger and more efficient democratic institutions. But how to do it? How to trigger their interest in understanding politics? This is precisely why effective accountability processes are important. With a more available, up to date, and validated information, citizens can participate in the public sphere. Open and public debates incentivize a major interest in the daily socio-political events in which each one of the members of the society is immersed or affected by. Furthermore, it is through the identification of the contemporary social, political and economic issues that an informed, participative and challenging civil society, capable of working in synergy with the government, emerges.

The existing accountability process in Mexico is far from perfect; in fact, there have been some corruption claims inside the institution. However, in such a maturing democratic system, it has allowed government and society to improve, or at least attempt to progress in the provision of public services, apply a fairer system of justice, and provide or demand a better (and achievable) level of life, something unimaginable just years ago. It is due to this accountability policy that the Mexican society now has a clearer, unfortunately still not perfect, knowledge about the number and names of drug traffickers caught (http://bigstory.ap.org/article/mexico-releases-list-top-arrested-narcos), or even corrupt practices inside government agencies, such as the use of public funds to buy expensive towels by a former president (http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/1399825.stm).

This, therefore, make us think that accountability can promote political punishment or cynicism from the population; but also, an opportunity for improvement of political processes. With major, but mostly, efficient levels of accountability, it could be possible to envisage a political where politicians do not feel the need, but more importantly, cannot make unfeasible promises; and where more informed citizens shift from being passive recipients or consumers of public goods, into politically responsible actors.