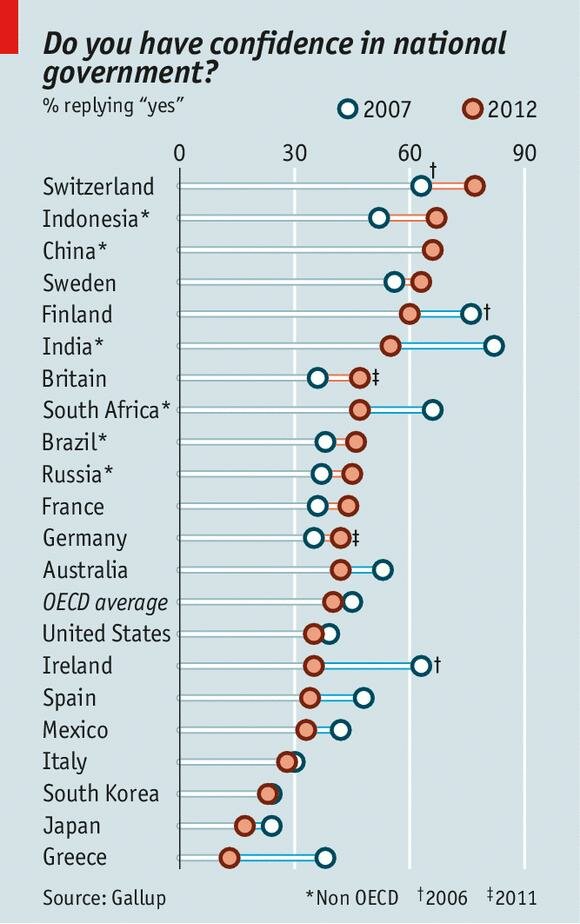

David Blunkett offers some compelling reasons why we should defend our traditional democratic institutions. But are they increasingly distant compared to people’s everyday social and political lives? Matt Wood suggests we need to investigate new forms of participation and ‘everyday politics’ to address the paradoxes of disengagement.

David Blunkett’s Policy & Politics lecture is a lucid and reflective statement on many of the paradoxes that we find in contemporary politics. As has become somewhat of a mantra for our times in academic circles, he notes that many British people are incredibly disillusioned with and disengaged from traditional democratic institutions. But he goes a bit further than this, noting that people make unrealistic and contradictory demands of government and that these put politicians in an unenviable position of having to ‘please all of the people all of the time’. People want conviction politicians like Tony Benn or Margaret Thatcher, but they also want an end to ‘Punch and Judy’ politics and ‘common sense’ governing where the solutions, apparently, everyone agrees on. This makes things doubly difficult for addressing disengagement because the causes of the problem are often as contradictory and confusing as the various solutions.

What should be done, then? For Blunkett, the first point is not to resort to extremism. He argues passionately that as a society we should resist the temptations of David Graeber’s ‘anarcho-populism’ and the politics of Russell Brand. Simply ‘taking to the streets’ will be destructive and regressive, as any glance at the history of revolutionary politics tells us. Instead, we should all try and be more understanding and less hateful of politics and politicians. Politics, Blunkett notes, is a deeply civilizing and uplifting practice. Politics may not be perfect, but has been necessary to achieve some of the great social advances of the twentieth century (and hopefully will be the same in the twenty-first century). As he rightly notes, establishing and maintaining those formal political institutions that we in Britain take for granted is critically important for consolidating the gains made in the Arab Spring and to avoid the horrific bloodshed in countries like Syria. Blunkett mentions Bernard Crick’s famous book ‘In Defence of Politics’ as a brilliant statement of precisely this point, and Matthew Flinders’ update of the book, ‘Defending Politics’, makes a similar argument for the twenty-first century. The media, the market and meretricious, Brand-esque figures are in danger of doing down the social, economic and cultural benefits that we gain from our stable Parliamentary democracy, despite all its faults.

Is it enough though simply to defend the old system when, as Blunkett mentions towards the end of his speech, people are still often interested and engaged in political issues, they just might act on that interest in different ways? In fact, as a lot of current research shows, we may be seeing a real sea-change in how people engage with and try to solve what they see as the big political issues. Political scientists have a number of words for this type of behaviour, but a good way of summing it up is the term ‘everyday politics’. People doing everyday politics know all the values Crick defended are important, but they also know that new technology can be utilised to drive change outside the formal system. They do politics when they like, where they like and how they like. This might be on the internet, through a local community project, a charity, or boycotting unethical corporate brands (some people see boycotting the BBC by not buying a TV as a political statement!). These people might vote occasionally, when they get time out of their busy lives, but they don’t see voting as the best way to get things done. They’re similarly turned off by party politics, which strikes them as too narrow or obsessed with media spin, or by Parliament, which seems dispiritingly anodyne and idiosyncratically outdated.

There are, of course, a number of paradoxes and inconsistencies here as well. People might ‘act locally and think globally’, but does that really make any difference? Everyday politics is often sporadic, disorganised and consumer-driven. While people might think they can do more by acting ‘closer to home’ rather than with the system, are we in danger of throwing the democratic baby out with our institutional bathwater? Would it really be better if the NHS was organised on a part-time ‘do-it-yourself’ basis? We think not. Traditional democratic institutions clearly do, and should have a place, as Blunkett makes clear. What we do think is these new forms of participation aren’t going to go away soon, and that simply defending the old system isn’t necessarily enough if we’re going to improve politics for the twenty-first century.

The challenge for us at the Crick Centre as we embark on an exciting programme of research is delving into how people live their political lives in the twenty-first century. While there’s already a lot of research out there on alternative forms of participation, we think there needs to be more into how and why there is a disconnection between people’s increasingly busy and congested everyday lives and the slow, churning world of ‘big-P’ Politics. Once we understand this better, we can begin to address how the institutions we should cherish (our national and regional parliaments, political parties and local councils) can evolve and adapt to our paradoxical political world.

Matt is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Sheffield Department of Politics, and Deputy Director of the Sir Bernard Crick Centre for the Public Understanding of Politics. He is currently researching ‘everyday politics’ and solutions to political disengagement in advanced liberal democracies.